Introduction

It’s never been more urgent for the chemicals and energy sectors to act with purpose, and those of us within the industry know it.

The approach to sustainability taken by these sectors has undeniably undergone a sea change, with widespread acceptance of the need for purposeful action.

But knowing change is needed and enacting it are two different things.

Both sectors are still largely fossil fuel dependent, and are negatively associated with crucial environmental issues, like CO2 emissions and plastic waste.

Perhaps counterintuitively, the fact companies in the industry could make radical operational changes means they are well-placed to have a positive environmental impact, as long as the cost of having this impact is itself sustainable.

In our survey of more than 1,000 chemical and energy companies across seven sub-sectors in five continents, we found that 97% have environmental impact reduction targets.

Nevertheless, our survey reveals that parts of the industry may be underestimating the size of the challenge, and the necessary steps to avert a climate disaster.

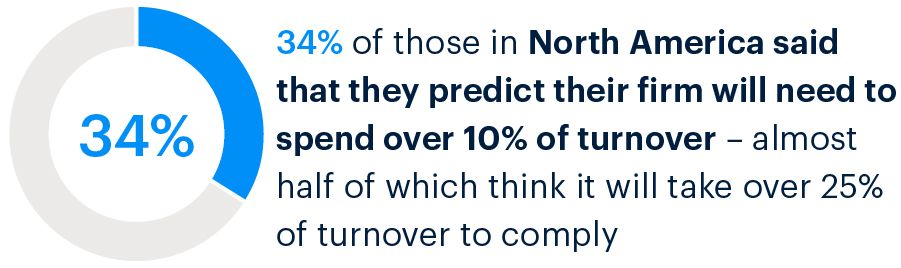

Some of this perceived inaction could be fuelled by firms’ overly pessimistic view of the cost of compliance: One in five firms globally expect regulatory requirements linked to the environment to cost between 11-50% of turnover, while a fifth of US, Canadian and Japanese firms expect it to cost between 26-50% of sales.

This report takes the global pulse of the chemicals and energy sectors in terms of their motivations to transform their operations, the potential barriers to change, and their hopes for the future.

Defining purpose

Purpose is an extremely wide phrase that can be stretched to cover a vast array of positive actions.

For this report, we would characterise purpose as delivering on environmental goals in a way that is financially sustainable and acceptable to all stakeholders.

Nearly two thirds (64%) of the companies we surveyed across 18 countries said they are on track to meet their climate-related targets. While this figure is arguably encouraging, almost half of such businesses do not publicly publish their targets – which might allow critics to question how bold they are.

If targets are not courageous and transparent - aside from the potential catastrophic consequences for the planet - businesses risk further fuelling the already negative public perception of our industry.

They also risk attrition to competitors with a better environmental image, or alternative products, a particular issue for the plastics industry.

There are already several packaging firms that have begun switching to alternatives such as paper, cardboard and glass, despite these materials often having a heavier CO2 impact.

Reducing the negative environmental impacts of energy and chemical production requires collaboration throughout the supply chain, alongside regulatory frameworks.

Furthermore, careful consideration of the science is needed when it comes to material and feedstock selection in order to minimise climate impact.

These choices are seldom easy.

Ready for change

The notion of internal targets points to a wider issue about the rhetoric surrounding climate change: Few national or global initiatives are actually binding, meaning corporations do not currently have to meet goals set by governments across the world.

Regardless, more than a quarter of the companies we surveyed stated that ‘doing business with purpose’ was their single-biggest strategic priority for 2021, showing that there is a desire by firms to reduce their environmental impact.

But aims need to become actions, and it is by creating a clear strategy, part of which involves harnessing the power of data and emerging digital technologies, that chemicals and energy companies can accelerate their efforts towards achieving their green goals.

Being part of the chemicals and energy industry means we know companies are focusing on driving innovation to help them identify practical ways to reduce fossil fuel use, reduce plastic waste and curb CO2 emissions.

Overt strategies supported by data and analytics can help here, and should allow firms to improve their operational efficiency, expedite project planning, and assist decision-making, while also supporting the evolution of supply chains to help create a sustainable future.

Firms also have a responsibility to look beyond the boundaries of their organisations; they must push for standardised information so that approaches can be compared directly, help generate cradle-to-grave analysis of every potential material, and ensure consumers are educated about the pros and cons of each material to enable them to make informed decisions.

The pressure to do these things is only going to keep rising.

Defining purpose

Purpose is an extremely wide phrase that can be stretched to cover a vast array of positive actions.

For this report, we would characterise purpose as delivering on environmental goals in a way that is financially sustainable and acceptable to all stakeholders.

Nearly two thirds (64%) of the companies we surveyed across 18 countries said they are on track to meet their climate-related targets. While this figure is arguably encouraging, almost half of such businesses do not publicly publish their targets – which might allow critics to question how bold they are.

If targets are not courageous and transparent - aside from the potential catastrophic consequences for the planet - businesses risk further fuelling the already negative public perception of our industry.

They also risk attrition to competitors with a better environmental image, or alternative products, a particular issue for the plastics industry.

There are already several packaging firms that have begun switching to alternatives such as paper, cardboard and glass, despite these materials often having a heavier CO2 impact.

Reducing the negative environmental impacts of energy and chemical production requires collaboration throughout the supply chain, alongside regulatory frameworks.

Furthermore, careful consideration of the science is needed when it comes to material and feedstock selection in order to minimise climate impact.

These choices are seldom easy.

Ready for change

The notion of internal targets points to a wider issue about the rhetoric surrounding climate change: Few national or global initiatives are actually binding, meaning corporations do not currently have to meet goals set by governments across the world.

Regardless, more than a quarter of the companies we surveyed stated that ‘doing business with purpose’ was their single-biggest strategic priority for 2021, showing that there is a desire by firms to reduce their environmental impact.

But aims need to become actions, and it is by creating a clear strategy, part of which involves harnessing the power of data and emerging digital technologies, that chemicals and energy companies can accelerate their efforts towards achieving their green goals.

Being part of the chemicals and energy industry means we know companies are focusing on driving innovation to help them identify practical ways to reduce fossil fuel use, reduce plastic waste and curb CO2 emissions.

Overt strategies supported by data and analytics can help here, and should allow firms to improve their operational efficiency, expedite project planning, and assist decision-making, while also supporting the evolution of supply chains to help create a sustainable future.

Firms also have a responsibility to look beyond the boundaries of their organisations; they must push for standardised information so that approaches can be compared directly, help generate cradle-to-grave analysis of every potential material, and ensure consumers are educated about the pros and cons of each material to enable them to make informed decisions.

The pressure to do these things is only going to keep rising.

Assessing perspectives

Chemicals and energy companies must be at the vanguard of the world’s efforts to reduce our negative impact on the planet.

Encouragingly, ‘doing business with purpose’ was the single biggest business priority for the largest proportion of companies in our survey. A total of 26% of the 1,003 firms stated this, closely followed by ‘entering new markets’, which was the main motivation for a quarter of respondents.

The belief that purpose was the key business driver for 2021 was particularly strong in North America (encompassing the US, Canada and Mexico), with two fifths of firms selecting this, but was weakest in the United Arab Emirates (7%), and Japan and Malaysia (13%).

As the world economy continues to emerge from the coronavirus crisis, it’s notable that the fewest companies cited ‘recovering from the impact of the pandemic on our business’ as their main priority.

This view could change though if governments implement initiatives that simultaneously address the heightened focus on sustainability that has emerged during the pandemic and repair the public finances, such as Extended Producer Responsibility (EPR) schemes.

Boardroom debate

Globally, nearly two-fifths of the organisations surveyed believed discussions about purpose were a high priority and a genuine Board-level issue. China strides ahead here, with 83% of companies stating this, with the United Arab Emirates the next closest country with 59%.

Notably, though, these are markets with the least developed regulation to drive environmental sustainability.

Nearly half of organisations felt purpose was important, but that it was not a Board-level issue now.

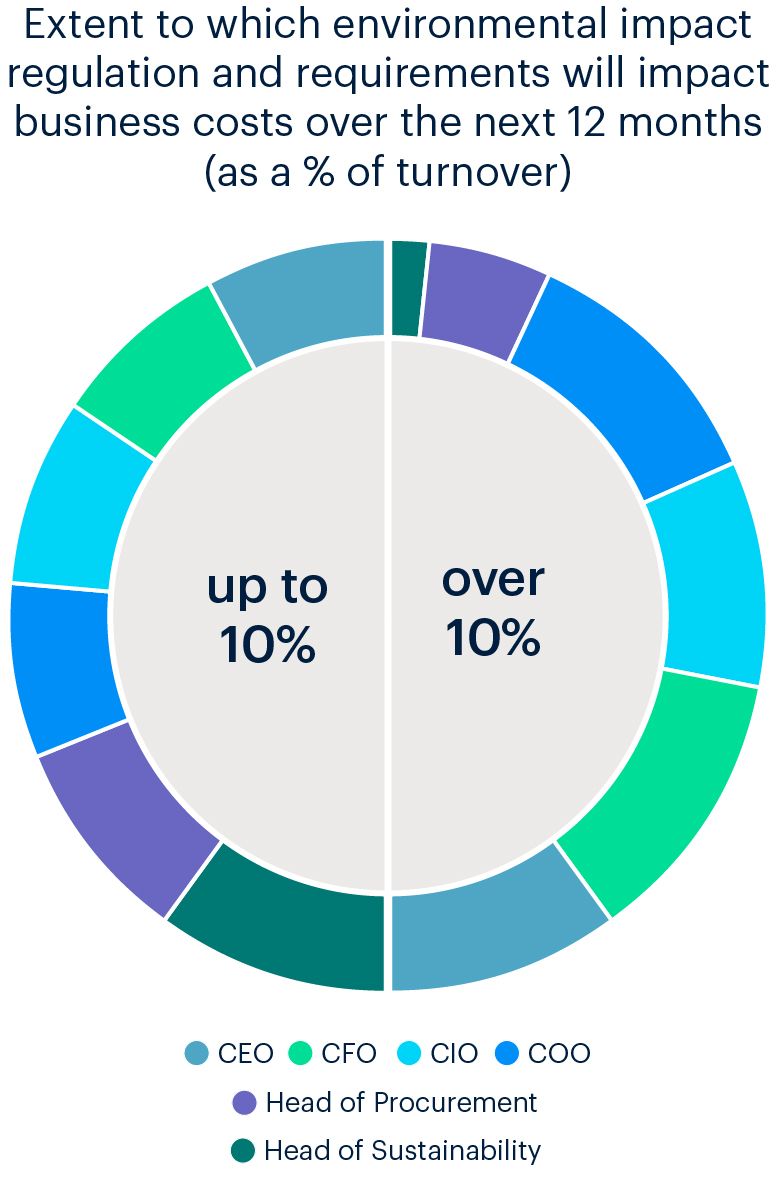

Intriguingly, the C-Suite is split here, with a higher proportion of chief operating officers, chief technology officers, and heads of sustainability viewing purpose as a Board-level issue. On the other hand, more chief executives, chief financial officers, chief investment officers, and heads of procurement agree it is important, but not a board-level concern.

This calls in to question whether measures will be backed by significant near-term investment.

Debatable targets

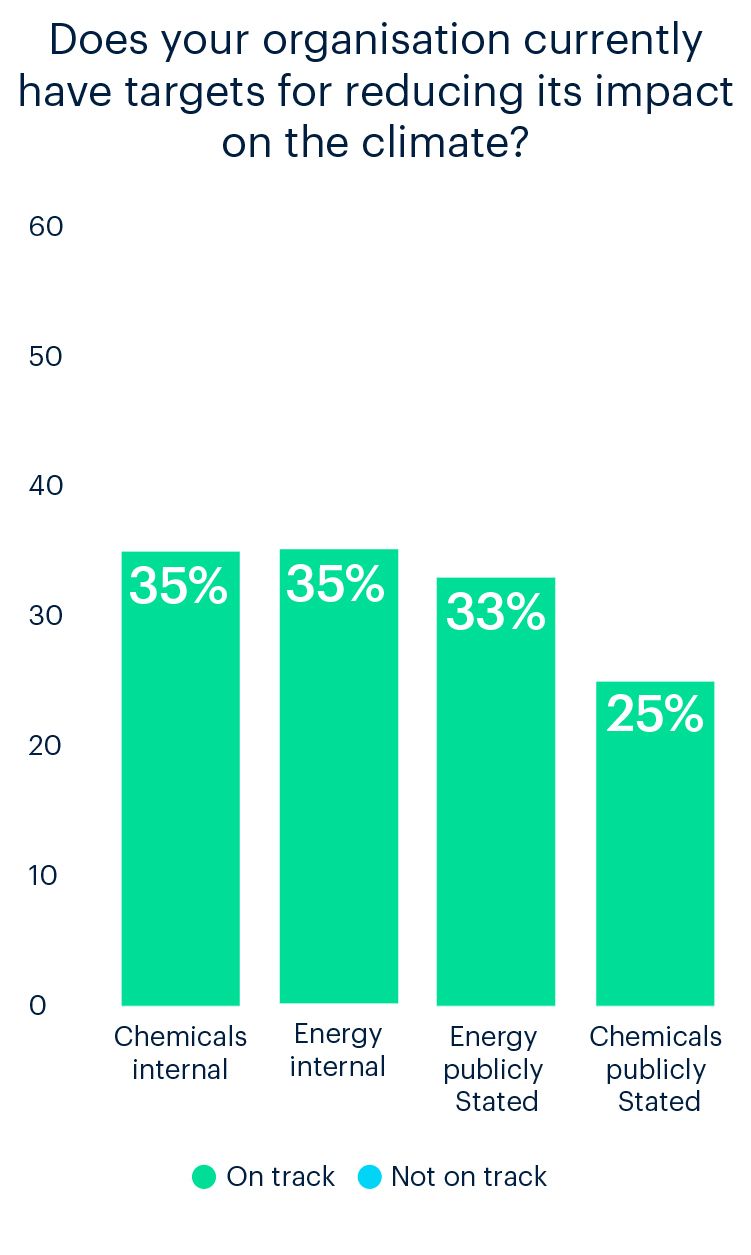

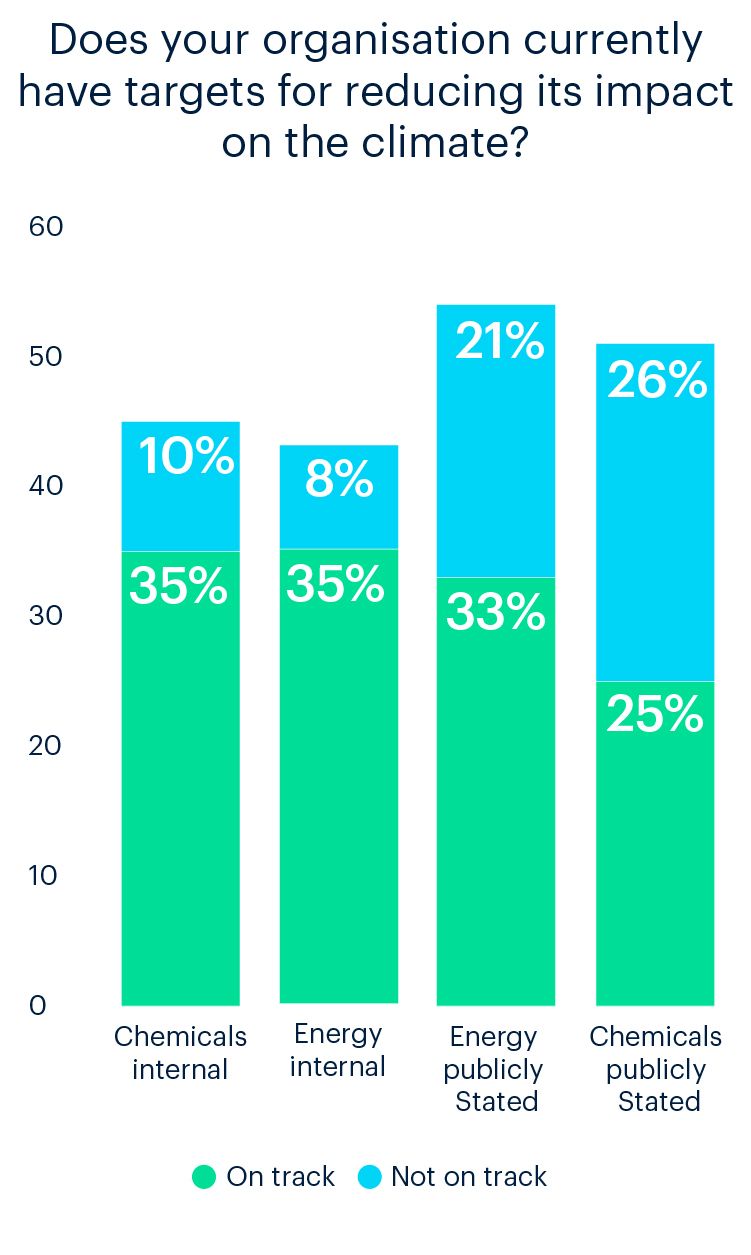

Regardless of the boardroom tussle over purpose, 97% of the companies surveyed have targets for reducing their organisation’s impact on the environment.

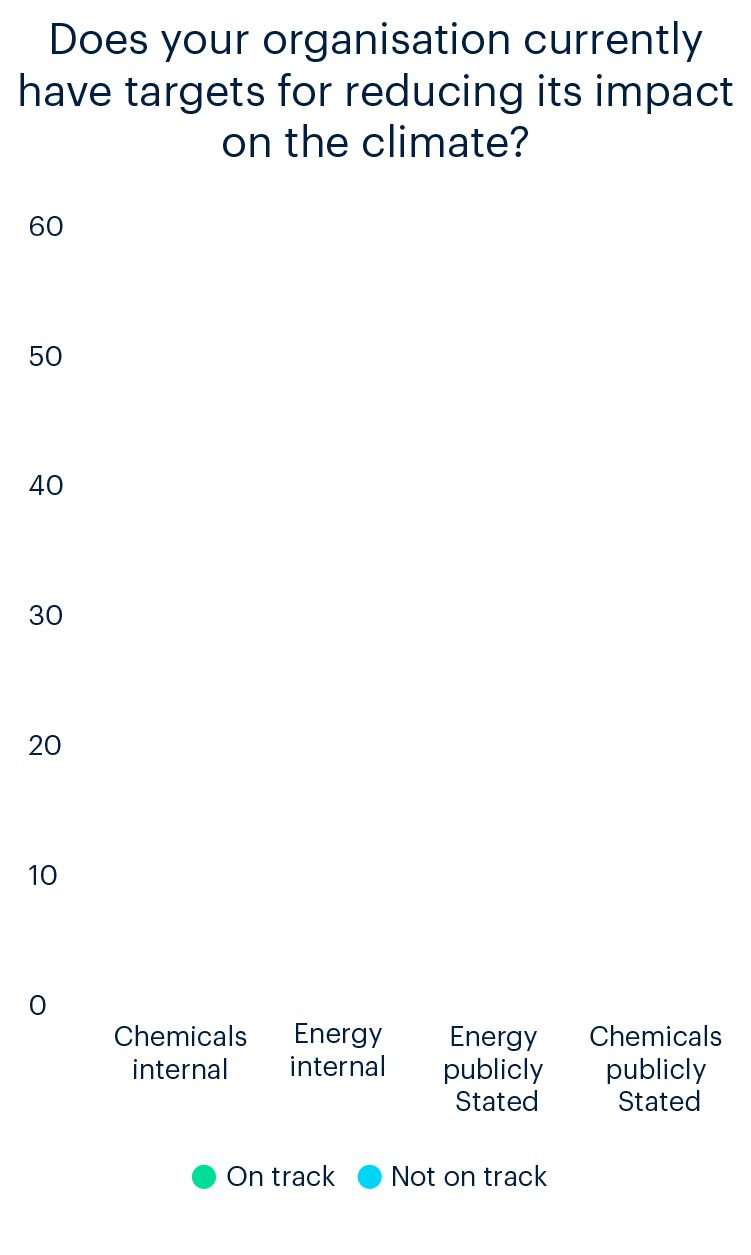

Nearly two thirds of companies said they are on track to meet their targets, but a small majority of these are purely internal hurdles.

On a sector level, a third of energy companies have public targets that they are on track to meet, whereas just a quarter of chemicals respondents could say the same. A larger proportion of companies in each sector are on track to meet their unpublished targets.

In terms of geography, companies in the US, China and Singapore are the most likely to publicly state their targets, while those in Brazil and the Middle East more commonly avoid public disclosure.

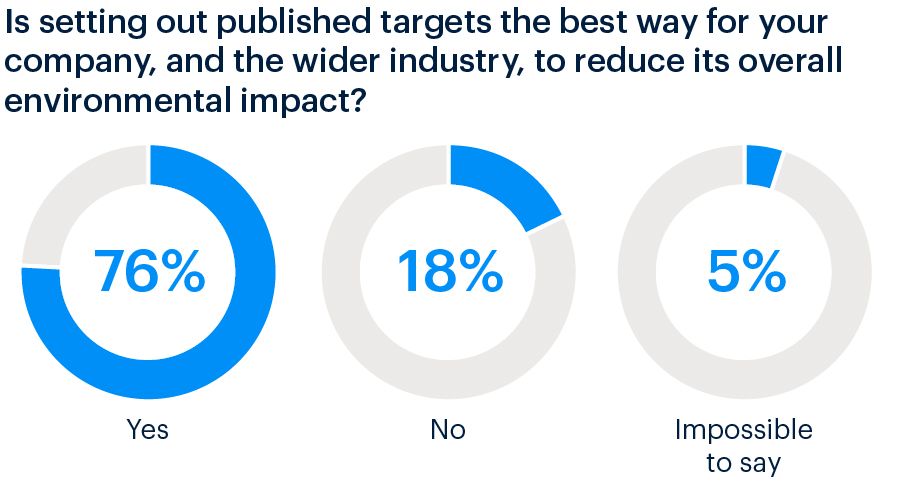

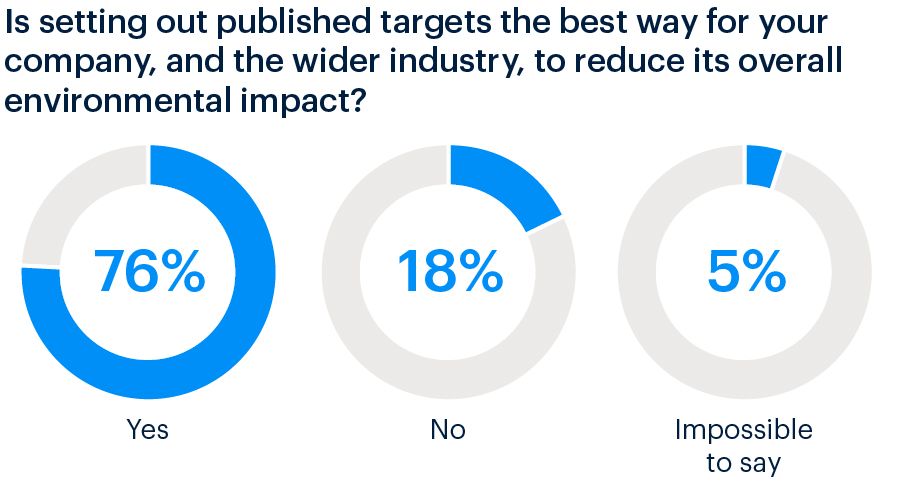

In spite of most companies globally eschewing public disclosure, more than three quarters of all firms surveyed acknowledged that overt targets were the best way to reduce their environmental impact, raising a question as to the efficacy of internal goals.

A fear about missing targets that are publicly stated could be one of the key barriers preventing our industry from being more open about its sustainability goals.

To overcome this, firms must quantify the pollution they create and develop strategies to tackle it across their business.

For any plan to be successful, companies must commit money and resources to its implementation, which will more than likely involve research, data, evidence-gathering, and embracing digitisation where it helps improve the efficiency of operations.

Collaboration with the entire supply chain is also necessary to prevent firms missing environmental goals, while embracing the likes of renewable fuels or recycled plastics – and fully understanding their supply, demand, and cost dynamics – is pivotal to success.

Recording and measuring the effect each change has on a firm’s environmental footprint is unquestionably vital.

Debatable targets

Regardless of the boardroom tussle over purpose, 97% of the companies surveyed have targets for reducing their organisation’s impact on the environment.

Nearly two thirds of companies said they are on track to meet their targets, but a small majority of these are purely internal hurdles.

On a sector level, a third of energy companies have public targets that they are on track to meet, whereas just a quarter of chemicals respondents could say the same. A larger proportion of companies in each sector are on track to meet their unpublished targets.

In terms of geography, companies in the US, China and Singapore are the most likely to publicly state their targets, while those in Brazil and the Middle East more commonly avoid public disclosure.

In spite of most companies globally eschewing public disclosure, more than three quarters of all firms surveyed acknowledged that overt targets were the best way to reduce their environmental impact, raising a question as to the efficacy of internal goals.

A fear about missing targets that are publicly stated could be one of the key barriers preventing our industry from being more open about its sustainability goals.

To overcome this, firms must quantify the pollution they create and develop strategies to tackle it across their business.

For any plan to be successful, companies must commit money and resources to its implementation, which will more than likely involve research, data, evidence-gathering, and embracing digitisation where it helps improve the efficiency of operations.

Collaboration with the entire supply chain is also necessary to prevent firms missing environmental goals, while embracing the likes of renewable fuels or recycled plastics – and fully understanding their supply, demand, and cost dynamics – is pivotal to success.

Recording and measuring the effect each change has on a firm’s environmental footprint is unquestionably vital.

Being a leader in our increasingly digital world is inextricably linked to data and automation.

Creating systems to collect data is important, but being able to analyse data and make informed decisions from it enables firms to excel, and being able to harness the power of artificial intelligence – or more simply, automating a manual process – can allow a business to improve its productivity.

Energy and chemicals firms are making significant progress here, according to our survey. More than half of respondents globally stated they are automating traditional industrial practices using data and smart technology, with more firms in Germany (62%), the Middle East and Brazil (both 59%) identifying new ways to operate.

This shift is overwhelmingly and uniformly being driven by those atop their organisations. The majority of executives within the C-Suite stated their firm was automating manual tasks, with more than two-thirds of heads of procurement selecting this option.

Within the industries themselves, chemicals manufacturers were most likely to be automating manual tasks (60%), while in energy, utility companies appear most active in this area (52%).

However, just 3% of firms globally have created a dedicated data science team, meaning there is an appetite for companies to hire specialist talent as digital transformation picks up pace across the chemical and energy industries. UK and Asian firms are most likely to have created bespoke data teams, with a quarter of the 24 Japanese firms surveyed handing this task to a specific group of workers.

There is no one-size-fits-all explanation as to why so few firms have developed specialist data teams, but the broader costs related to embedding ESG measures into a company’s operations and strategy could be among the main impediments.

Organisations increasingly want to take proactive steps towards becoming more sustainable enterprises, but this costs both time and, perhaps most importantly, money.

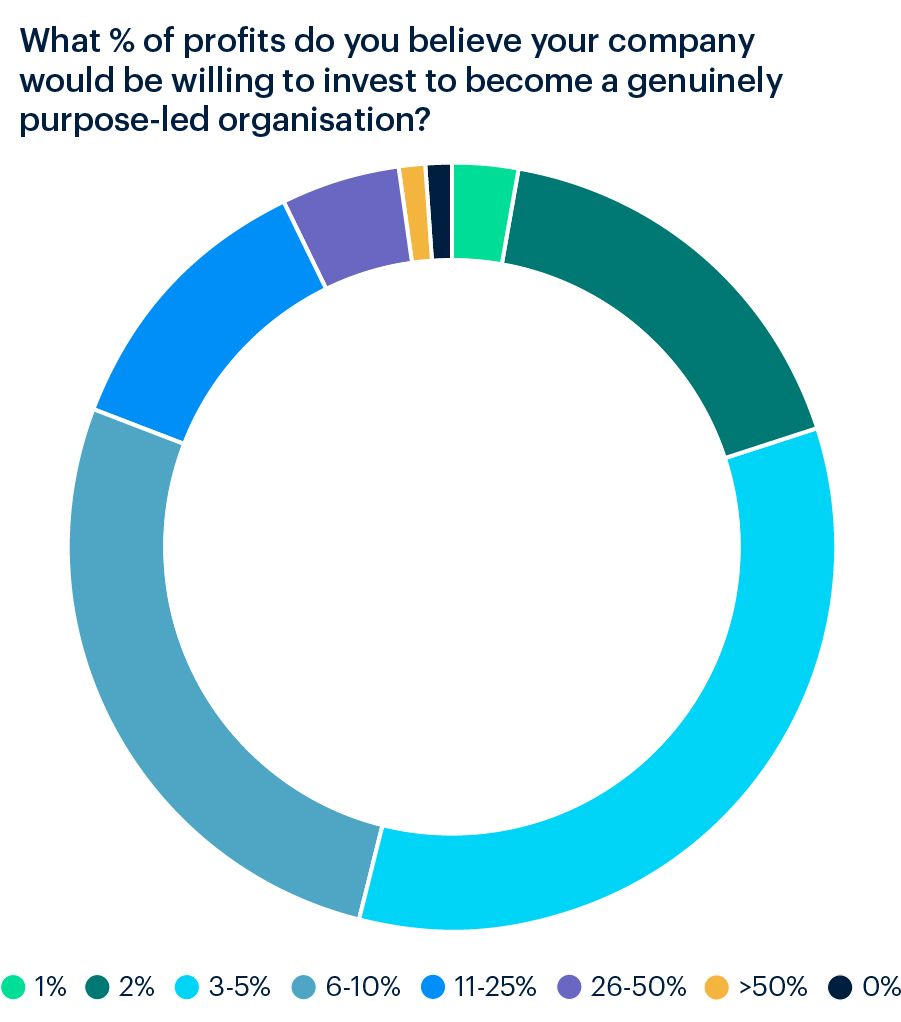

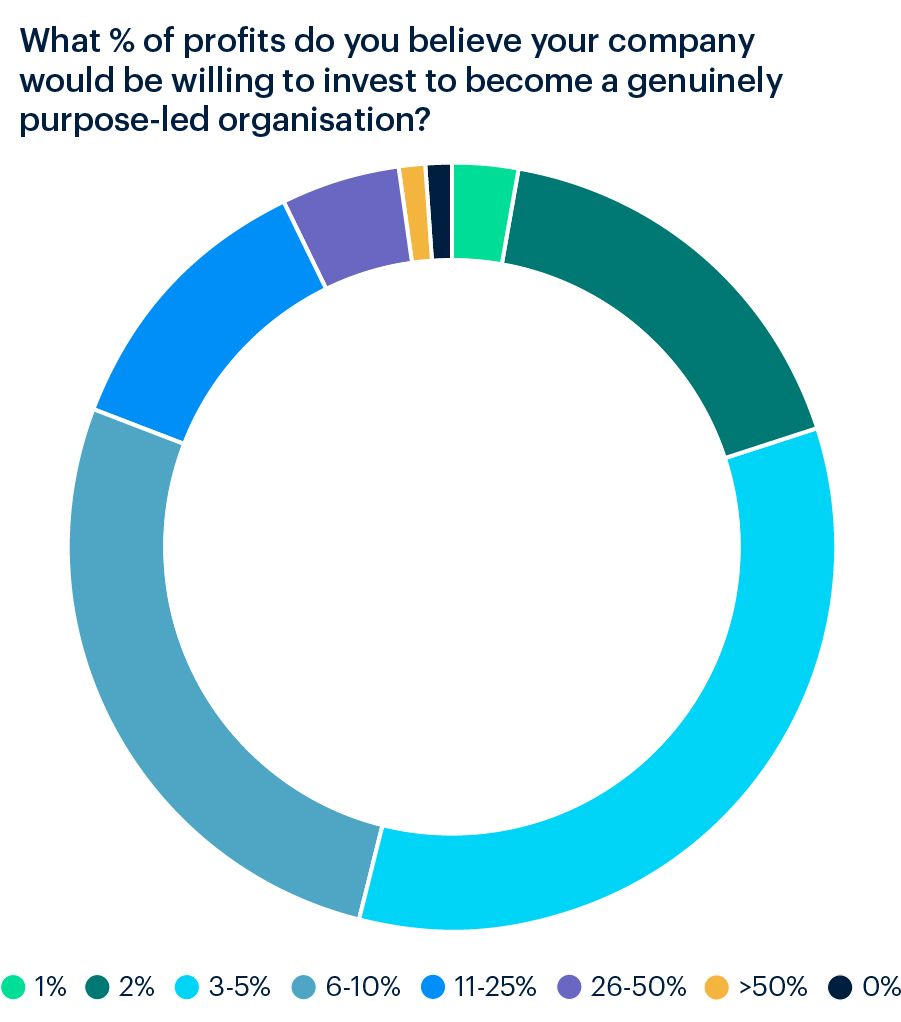

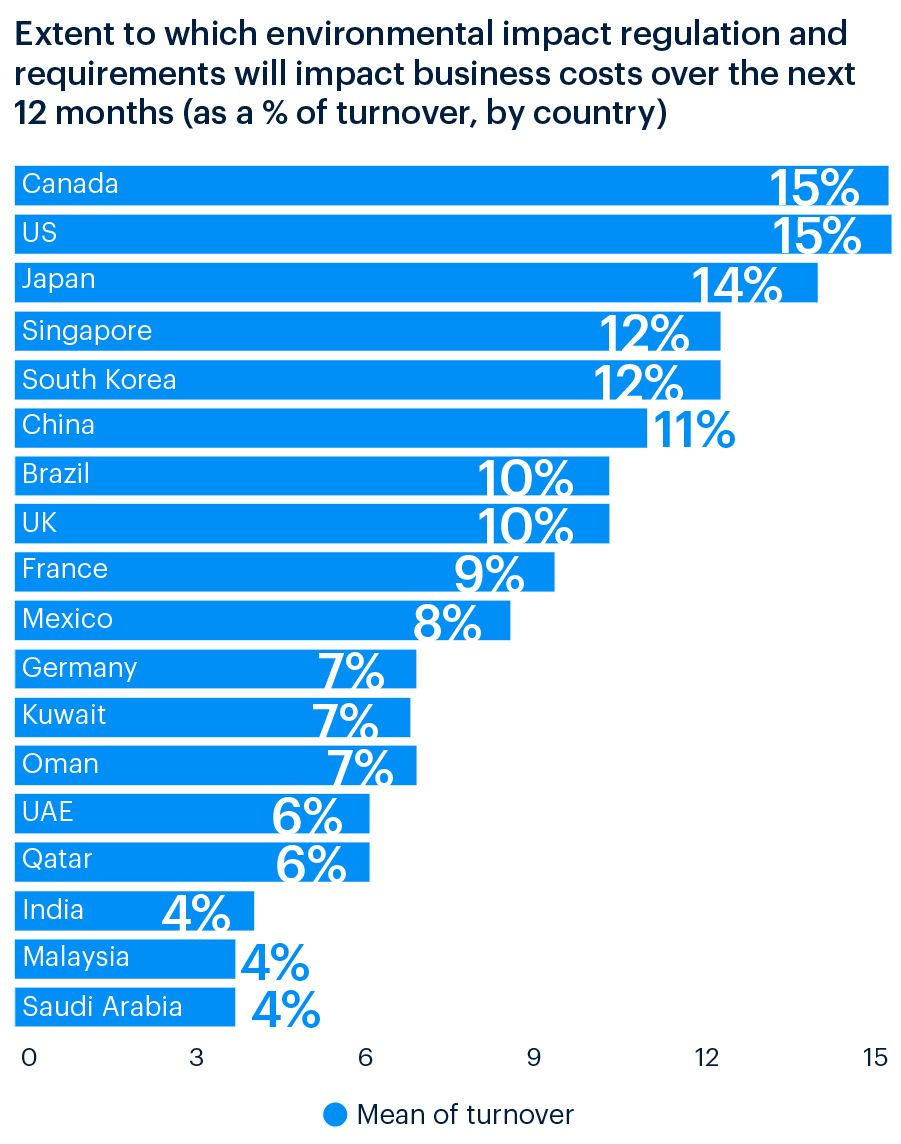

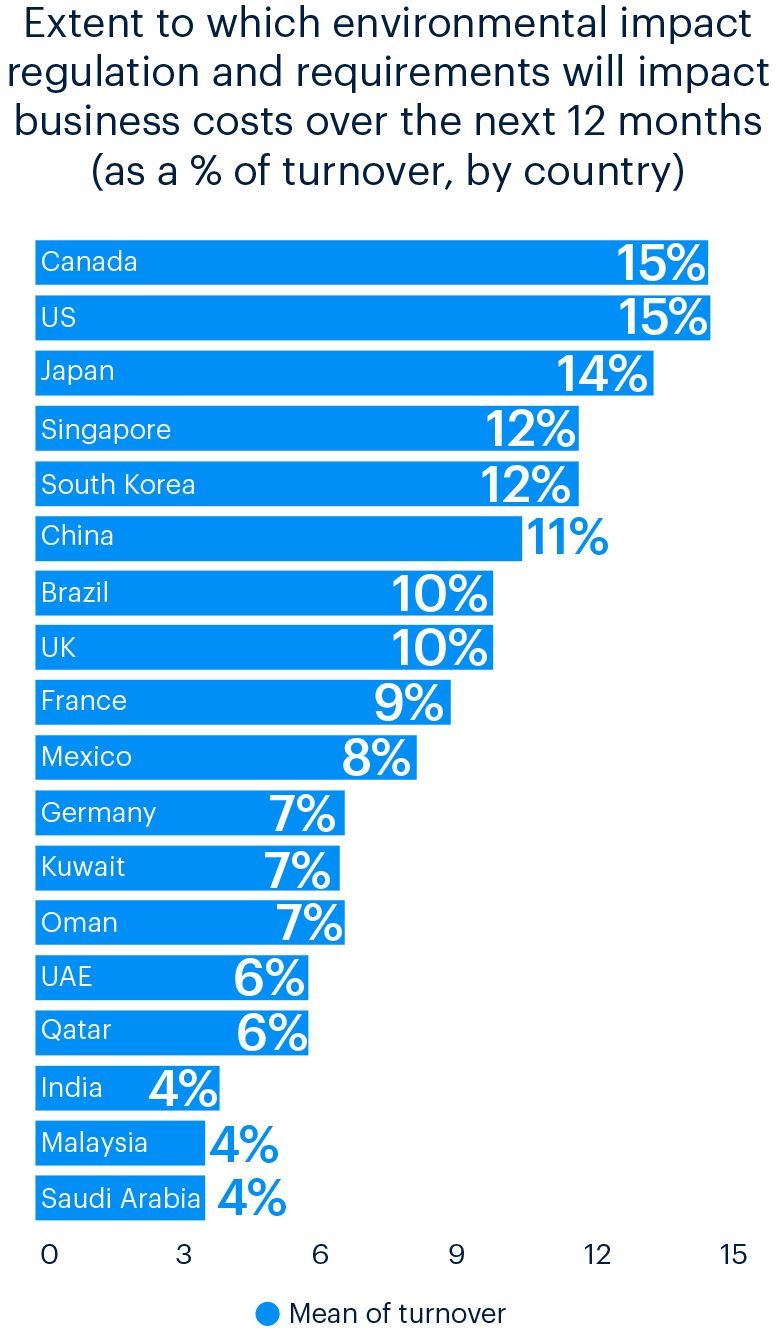

More than a third of firms surveyed believed they would need to spend between 3% – 5% of turnover in the next 12 months to satisfy the regulatory requirements related to environmental impact, while 26% of firms expected this to be between 6% and 10%.

Remarkably, over 1 in 5 firms thought they would have to spend more than 10% of their annual turnover.

Businesses in Asia and the Middle East were most likely to predict changes would cost 3% – 5% of turnover, while firms in the UK were more likely than those in other countries to expect changes to cost 6% – 10%.

In Canada, there is a strong belief these costs will be higher, with the most firms there (30%) expecting the changes to cost 11% – 25% of turnover, a view shared by 29% of firms in Singapore and a quarter of Chinese companies.

Organisations increasingly want to take proactive steps towards becoming more sustainable enterprises, but this costs both time and, perhaps most importantly, money.

More than a third of firms surveyed believed they would need to spend between 3% – 5% of turnover in the next 12 months to satisfy the regulatory requirements related to environmental impact, while 26% of firms expected this to be between 6% and 10%.

Remarkably, over 1 in 5 firms thought they would have to spend more than 10% of their annual turnover.

Businesses in Asia and the Middle East were most likely to predict changes would cost 3% – 5% of turnover, while firms in the UK were more likely than those in other countries to expect changes to cost 6% – 10%.

In Canada, there is a strong belief these costs will be higher, with the most firms there (30%) expecting the changes to cost 11% – 25% of turnover, a view shared by 29% of firms in Singapore and a quarter of Chinese companies.

Sector specifics

Within the industries themselves, distributors in the chemicals sector are most likely to believe they will need to spend 3% – 5% of turnover, while 64% of producers are most likely to believe it will cost between 3% – 10%.

For energy firms, refineries are most likely to believe they will have to set aside 3% – 5% of turnover, while more utilities companies expect to spend between 6% – 10% than their peers in other sub-sectors.

Every job type in the C-Suite, except the CTO, was most likely to predict that businesses would need to spend 3% – 5% of turnover, perhaps suggesting this could be a global average in the next 12 months.

It’s impossible to know how much firms should spend or how much will actually be required, but it does highlight that firms expect regulatory pressure on sustainability to remain high given elevated, and rising, levels of public scrutiny upon them.

There is an incongruity between the size of the expected expenditure to meet basic regulatory requirements and the percentage of firms that say they are on track to meet their sustainability targets.

This suggests either that regulation goes far beyond internal targets, or that progress has been slower than many firms are prepared to admit.

Sector specifics

Within the industries themselves, distributors in the chemicals sector are most likely to believe they will need to spend 3% – 5% of turnover, while 64% of producers are most likely to believe it will cost between 3% – 10%.

For energy firms, refineries are most likely to believe they will have to set aside 3% – 5% of turnover, while more utilities companies expect to spend between 6% – 10% than their peers in other sub-sectors.

Every job type in the C-Suite, except the CTO, was most likely to predict that businesses would need to spend 3% – 5% of turnover, perhaps suggesting this could be a global average in the next 12 months.

It’s impossible to know how much firms should spend or how much will actually be required, but it does highlight that firms expect regulatory pressure on sustainability to remain high given elevated, and rising, levels of public scrutiny upon them.

There is an incongruity between the size of the expected expenditure to meet basic regulatory requirements and the percentage of firms that say they are on track to meet their sustainability targets.

This suggests either that regulation goes far beyond internal targets, or that progress has been slower than many firms are prepared to admit.

Regulatory pressure

Regulators are forcing the de-carbonisation of the energy markets, fundamentally changing the way in which energy is created and used. As such, the pressure to be on the right side of forthcoming regulations is great.

This perhaps explains why more than two-fifths of respondents globally state that ESG disclosure regulations, which require the publication of data to reveal the impact of a business in ESG terms, are the biggest regulatory risk facing their firm today.

More than half of German companies believed this, while 47% of firms in Brazil and 43% in the Middle East concurred. Although only 37% of Asian firms had this view, the regional figure masks wide country-specific figures, with Malaysia (65%) and China (63%) expressing great concern about disclosure regulations, while the issue seemed less problematic in India (8%) and South Korea (13%).

Only a third of UK firms were concerned about ESG disclosure, and businesses there were the third most likely (behind Qatar and Singapore) to claim they did not perceive any ESG regulatory risks for their business.

Companies in the US were more fearful than others about the EU Ecolabel framework, which identifies sustainable products for consumers with the ultimate aim of creating a circular economy.

This either means that US firms believe there are significant challenges ahead in order to contribute towards sustainable production and consumption, or that companies in other countries are being over-optimistic about their progress so far.

Owning the issue

The crucial thing most firms in our industry globally do agree on is that the burden to steer the planet to a sustainable future does not predominantly fall on consumers, but requires a top-down approach.

This shows that energy and chemical firms are increasingly recognising how to help tackle the climate emergency.

Nearly half of respondents believed lawmakers and regulators had the biggest responsibility to tackle climate change, while just over two-fifths of those surveyed believed the responsibility lay with companies like themselves.

Just 10% of firms felt consumers and businesses had the biggest responsibility when it came to reducing the climate impact of their products or those of the wider industry.

However, there are large geographic disparities, and it’s difficult to know how these might help or hinder an individual country’s progress: Nations where people predominantly believe consumers shoulder the greatest burden to reduce emissions might see slower progress on reductions, but a greater belief that lawmakers need to act doesn’t necessarily mean they will.

Businesses in US were by far the most likely to say it was their responsibility to reduce the climate impact of their products, with 86% stating so.

Historically, firms have been criticised for arguing that managing the climate change impacts of their products is the responsibility of the consumer, or government. The results of this survey point to a generational shift occurring within the industry and an acceptance that change is necessary.

Respondents in Brazil and the Middle East were most likely to put responsibility for the necessary changes on their respective governments, with 69% of firms in the UAE stating this, 68% in Oman, and 63% in Brazil.

Motivations for change

The same percentage of firms that believe it is their responsibility to drive change in this area – 41% – are doing so because it is morally correct, as opposed to profitability, regulation or stakeholder pressure, according to our survey.

This is the reason selected by most firms globally when asked to state their biggest incentive for becoming more sustainable, with nearly two-thirds of businesses in Oman saying this, half of businesses in the US, and 48% of companies in France, Kuwait and Malaysia agreeing.

Nearly a quarter (23%) state that increased profitability is their main incentive for becoming more sustainable, with companies in the UAE most likely to cite this as the key driver, and just 8% of companies in the United States being spurred on by profit – the lowest level of any country surveyed.

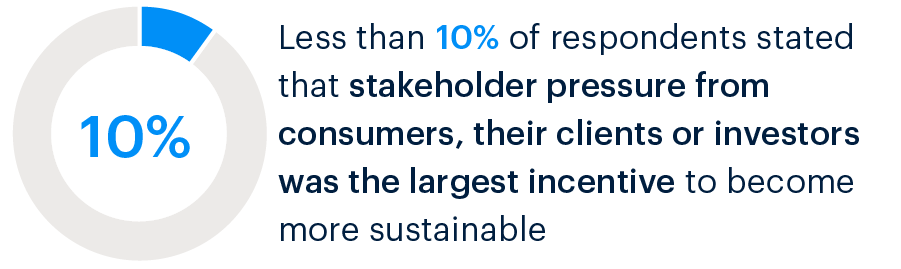

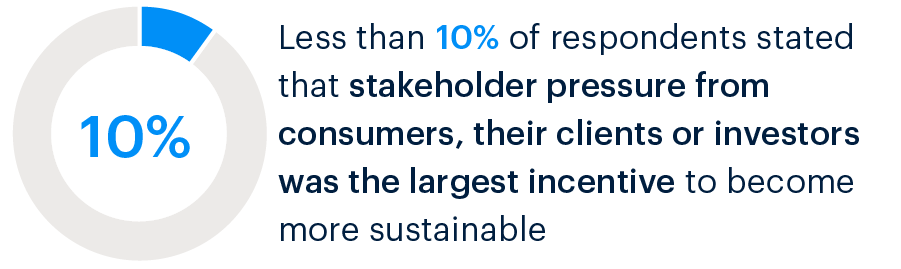

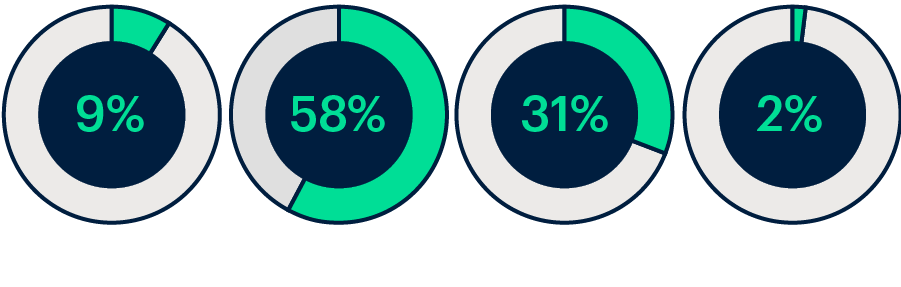

Pressure from stakeholders – such as investors and customers – appears not to be a major catalyst for firms, with just 9% of businesses globally stating this as their main reason for becoming more environmentally friendly.

Regulations, however, are the biggest provoking factor for more than a fifth of firms (21%), something most feared by businesses in the US (42%), the UK and Mexico (both 29%).

Nevertheless, given the intrinsic link between profitability and consumption, consumer behaviour can still be seen as one of the major drivers towards the sector adopting sustainability measures.

Within sub-sectors, the largest proportion of chemicals traders believe moves to become more sustainable are driven by the potential for increased profitability, and are least likely to be driven by a moral imperative compared to other chemicals sub-sectors.

In energy, nearly half of utilities companies (48%) believe becoming more sustainable is morally correct, whereas refineries are most likely to be driven by regulations.

Motivations for change

The same percentage of firms that believe it is their responsibility to drive change in this area – 41% – are doing so because it is morally correct, as opposed to profitability, regulation or stakeholder pressure, according to our survey.

This is the reason selected by most firms globally when asked to state their biggest incentive for becoming more sustainable, with nearly two-thirds of businesses in Oman saying this, half of businesses in the US, and 48% of companies in France, Kuwait and Malaysia agreeing.

Nearly a quarter (23%) state that increased profitability is their main incentive for becoming more sustainable, with companies in the UAE most likely to cite this as the key driver, and just 8% of companies in the United States being spurred on by profit – the lowest level of any country surveyed.

Pressure from stakeholders – such as investors and customers – appears not to be a major catalyst for firms, with just 9% of businesses globally stating this as their main reason for becoming more environmentally friendly.

Regulations, however, are the biggest provoking factor for more than a fifth of firms (21%), something most feared by businesses in the US (42%), the UK and Mexico (both 29%).

Nevertheless, given the intrinsic link between profitability and consumption, consumer behaviour can still be seen as one of the major drivers towards the sector adopting sustainability measures.

Within sub-sectors, the largest proportion of chemicals traders believe moves to become more sustainable are driven by the potential for increased profitability, and are least likely to be driven by a moral imperative compared to other chemicals sub-sectors.

In energy, nearly half of utilities companies (48%) believe becoming more sustainable is morally correct, whereas refineries are most likely to be driven by regulations.

Assessing the impact

Utility companies may more commonly be driven by morals when it comes to sustainability due to their large retail customer base, a cohort that is increasingly aware of climate change, and of the effect their consumption has on the planet.

With utilities such as electric companies, this could be related to consumers wanting their energy to be largely or entirely generated from renewable sources.

Those who can deliver against this consumer demand are likely to be rewarded with growing customer numbers.

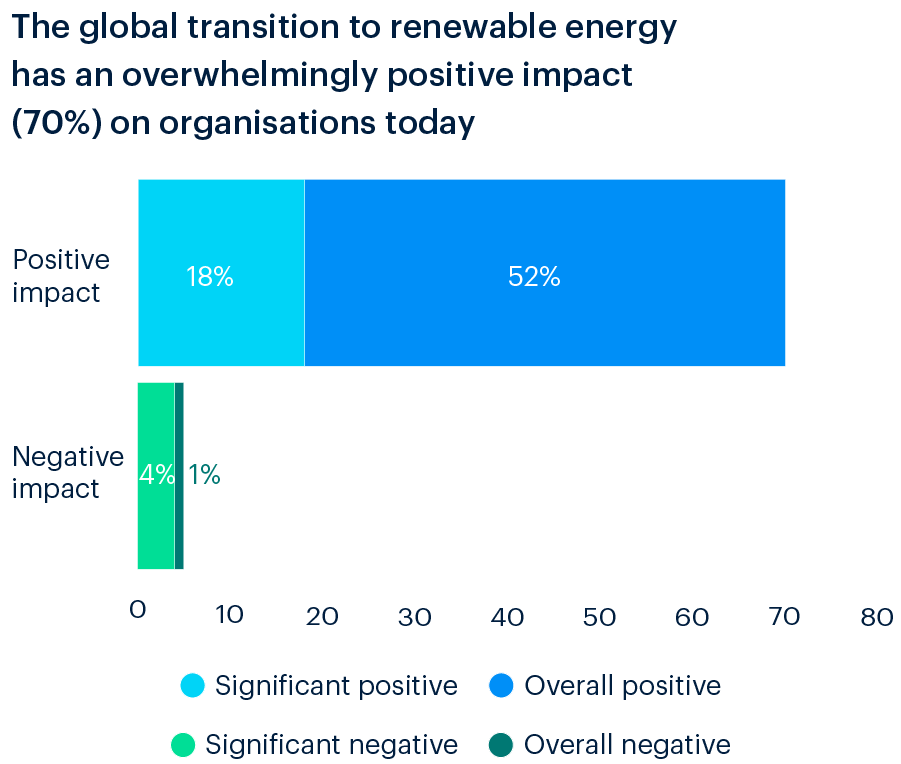

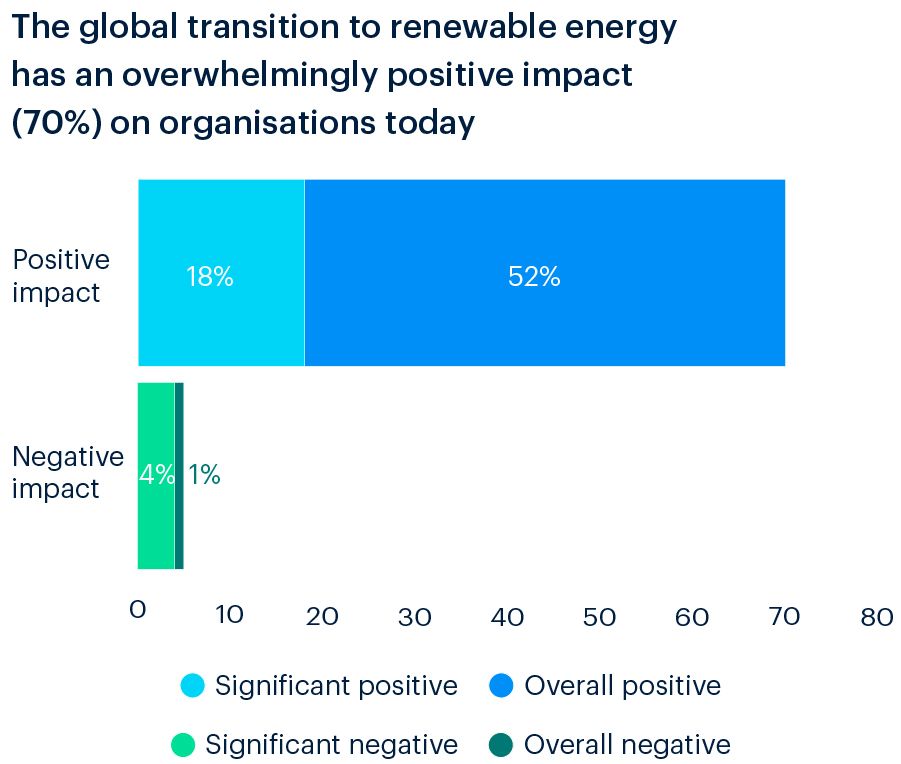

This might explain why 60% of utility companies surveyed believe the transition to renewable energy is having a positive impact on their organisation.

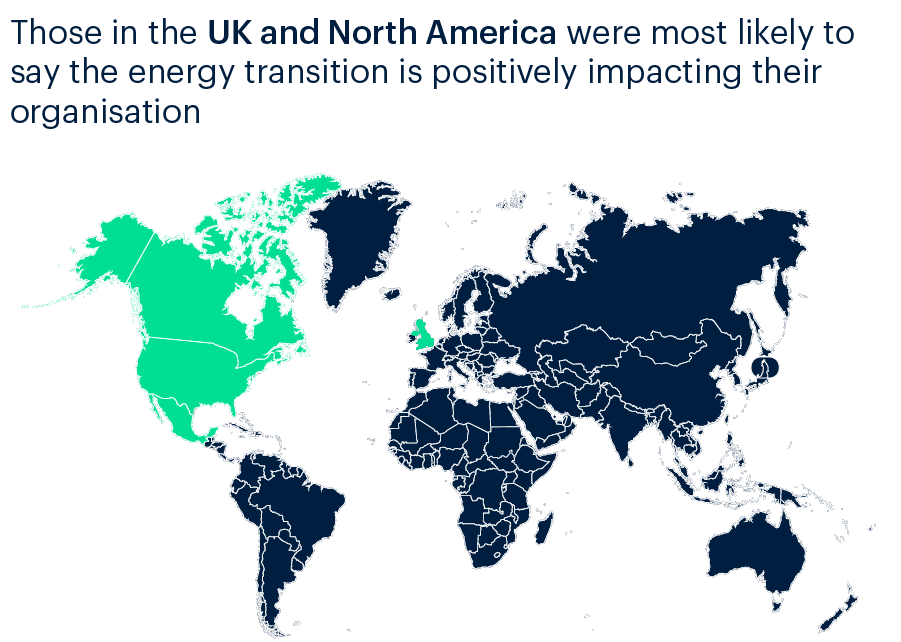

Looking globally, businesses in the UK and North America are most likely to claim the transition to clean energy is having a ‘significantly positive’ effect on their organisation but those in the Middle East (15%) and Germany (8%) are far more sceptical.

Meanwhile, firms in Brazil, Oman and China are the most likely to state that this shift is having a ‘positive’ impact, a view held by a majority (52%) of business owners globally.

Firms in Asia are more likely than those in the other countries surveyed to claim the energy transition is having a ‘negative’ impact on them, with one in 10 claiming this.

The rising pressure on firms – including from consumers and regulators – to act with positive purpose has forced brands to look at where and how they source raw materials.

This is most notable in plastics, where several multinational brands have made commitments to source recycled resin. Emissions reduction and circularity are becoming more pressing through the whole supply chain.

The short timeframes for implementation, and ambition of brand targets, will likely mean increased competition for material.

Assessing the impact

Utility companies may more commonly be driven by morals when it comes to sustainability due to their large retail customer base, a cohort that is increasingly aware of climate change, and of the effect their consumption has on the planet.

With utilities such as electric companies, this could be related to consumers wanting their energy to be largely or entirely generated from renewable sources.

Those who can deliver against this consumer demand are likely to be rewarded with growing customer numbers.

This might explain why 60% of utility companies surveyed believe the transition to renewable energy is having a positive impact on their organisation.

Looking globally, businesses in the UK and North America are most likely to claim the transition to clean energy is having a ‘significantly positive’ effect on their organisation but those in the Middle East (15%) and Germany (8%) are far more sceptical.

Meanwhile, firms in Brazil, Oman and China are the most likely to state that this shift is having a ‘positive’ impact, a view held by a majority (52%) of business owners globally.

Firms in Asia are more likely than those in the other countries surveyed to claim the energy transition is having a ‘negative’ impact on them, with one in 10 claiming this.

The rising pressure on firms – including from consumers and regulators – to act with positive purpose has forced brands to look at where and how they source raw materials.

This is most notable in plastics, where several multinational brands have made commitments to source recycled resin. Emissions reduction and circularity are becoming more pressing through the whole supply chain.

The short timeframes for implementation, and ambition of brand targets, will likely mean increased competition for material.

Aiming for circular

The target every company and country is striving for is to achieve circularity of resources. This would enable the recycling of plastic waste, keeping products and materials in use, and would relinquish the ‘take-make-dispose’ model we have used to date that absorbs the planet’s finite resources.

Our survey, which focused on chemicals companies for this issue, revealed some optimistic views on how long it will take to develop the required infrastructure to tackle the global issue of plastic waste.

Two thirds of chemicals firms believe it will take two years at the most to tackle the globe’s plastic waste problems, with German companies the most optimistic thanks to 17% of firms expecting it to take less than a year.

Companies in China (60%), Qatar (57%) and the UK (50%) are the most pessimistic, believing it will take 3-4 years, while firms in the UK are more likely than those in other nations to predict it will take more than 4 years.

Many chemical firms are not yet directly involved in the recycling sector, and these survey results suggests a lack of knowledge among chemical firms over the current state of waste collection capacity, along with an simplification of the challenges in expanding this capacity – including the ability of depleted public coffers to fund improvements, issues with contamination that hamper recycling rates, and the fact virgin capacity expansion continues to outpace the growth in recycling capacity.

This creates a significant risk of underinvestment from the sector.

It’s undeniable that firms in our industry are evolving and facing up to the pressure on them to become more sustainable.

The depth of feeling that the environmental impact firms have must be directly tackled, along with the desire for hard targets, may surprise many reading this survey.

It points to a generational shift occurring within the industry and an acceptance that change is necessary.

Nearly nine out of every 10 firms we surveyed globally has said they have a dedicated individual or team that is responsible for managing their energy transition.

Encouragingly, every Chinese respondent had this in place, while nearly every US firm (98%) did too. This is important given these two nations are by far the world’s single biggest emitters of CO2, and efforts by them to curb global warming are vital if the world is to hit climate targets.

Every organisation needs to play its part, so it’s encouraging that even in countries where dedicated teams were less prevalent, such as Germany and the Middle East, 80% of firms had given specific people or teams the responsibility for tackling this issue.

Whoever is navigating a firm’s quest for change, meaningful and informed targets are key.

Simply switching to an alternative energy source or embracing a recycled material won’t necessarily mean automatically hitting sustainability goals; businesses must truly understand the impact any potential change might have on their organisation.

Practicable steps that firms can take include building a detailed plan of how its desired objectives will be achieved, with contingencies built in to allow for unforeseen circumstances.

These objectives must then be published to maintain accountability, but also to ensure the entire supply chain can engage with any carbon-reduction efforts.

For true effectiveness though, a global standardisation of environmental impact assessments must be coordinated, with all the necessary information to inform firms’ sustainability and climate change initiatives.

And governments must widen their legislative net to cover all products that cause environmental harm to prevent consumers unwittingly switching to a process or product that is equally or even more pollutive than the existing one.

Business leaders may feel overwhelmed by the scale of the challenges ahead, but inactivity is not an option; firms must start acting immediately.

There are numerous reasons why, notably potential post-pandemic regulation, and competition for materials, new technology and customers.

Besides these possible near-term pressures, our industry must collaborate with regulators to ensure legislation assists rather than hinders the development of a sustainable and circular economy, it must adopt new technology that supports its aims, and it must push for binding targets that help create a level playing field with real accountability.

Our survey shows a willingness by firms to take action, and by taking proactive steps, companies can be confident their actions become purpose.

It’s undeniable that firms in our industry are evolving and facing up to the pressure on them to become more sustainable.

The depth of feeling that the environmental impact firms have must be directly tackled, along with the desire for hard targets, may surprise many reading this survey.

It points to a generational shift occurring within the industry and an acceptance that change is necessary.

Nearly nine out of every 10 firms we surveyed globally has said they have a dedicated individual or team that is responsible for managing their energy transition.

Encouragingly, every Chinese respondent had this in place, while nearly every US firm (98%) did too. This is important given these two nations are by far the world’s single biggest emitters of CO2 , and efforts by them to curb global warming are vital if the world is to hit climate targets.

Every organisation needs to play its part, so it’s encouraging that even in countries where dedicated teams were less prevalent, such as Germany and the Middle East, 80% of firms had given specific people or teams the responsibility for tackling this issue.

Whoever is navigating a firm’s quest for change, meaningful and informed targets are key.

Simply switching to an alternative energy source or embracing a recycled material won’t necessarily mean automatically hitting sustainability goals; businesses must truly understand the impact any potential change might have on their organisation.

Practicable steps that firms can take include building a detailed plan of how its desired objectives will be achieved, with contingencies built in to allow for unforeseen circumstances.

These objectives must then be published to maintain accountability, but also to ensure the entire supply chain can engage with any carbon-reduction efforts.

For true effectiveness though, a global standardisation of environmental impact assessments must be coordinated, with all the necessary information to inform firms’ sustainability and climate change initiatives.

And governments must widen their legislative net to cover all products that cause environmental harm to prevent consumers unwittingly switching to a process or product that is equally or even more pollutive than the existing one.

Business leaders may feel overwhelmed by the scale of the challenges ahead, but inactivity is not an option; firms must start acting immediately.

There are numerous reasons why, notably potential post-pandemic regulation, and competition for materials, new technology and customers.

Besides these possible near-term pressures, our industry must collaborate with regulators to ensure legislation assists rather than hinders the development of a sustainable and circular economy, it must adopt new technology that supports its aims, and it must push for binding targets that help create a level playing field with real accountability.

Our survey shows a willingness by firms to take action, and by taking proactive steps, companies can be confident their actions become purpose.