Clearing the air: Understanding Scope 3 Emissions for Chemical Markets

The data problem slowing down progress on climate targets in the chemical industry.

Climate change is the biggest challenge of our lifetime. Its impact on our basic needs – access to nutritious food, healthcare, shelter, safety, and clean environment – is increasingly evident. Likewise, to solve it will require a tremendous effort from society, governments, and businesses. Carbon emissions are the biggest contributor to climate change and the key to solving this challenge. However, accurately capturing the data related to emissions and transparently reporting it is equally important.

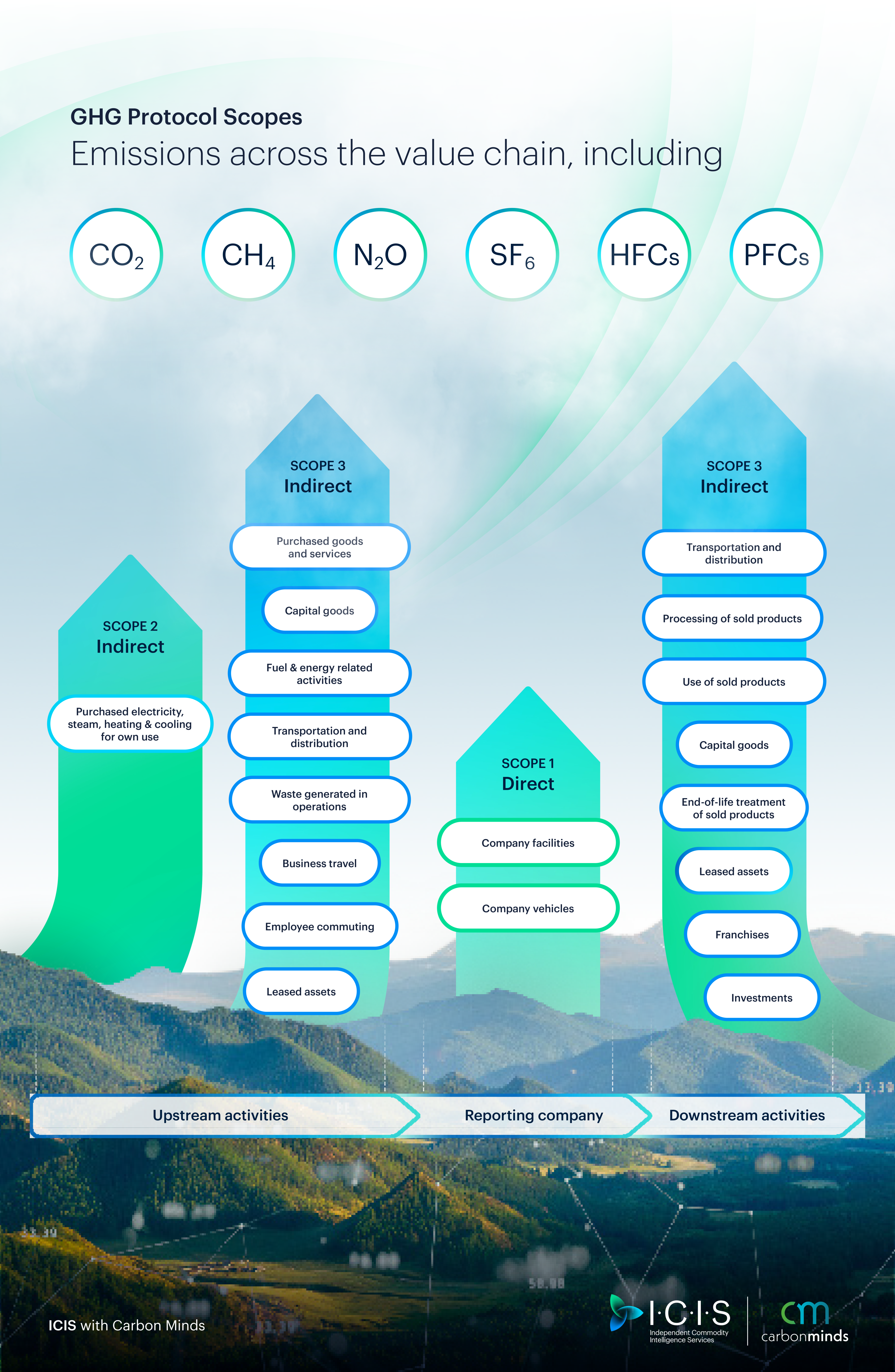

The chemical industry’s contribution to climate change mitigation is taking shape under the umbrella of ‘Net-Zero’. This means achieving net-zero emissions in the operations and supply chains of the industry and are usually reported as Scope 1 – direct emissions related to the company’s own operations, Scope 2 – direct emissions related to the utilities purchased by the company, and Scope 3, the most varied and challenging to report – indirect emissions related to both upstream and downstream activities. In 2021, as part of their contribution to Saudi Arabia’s national target to reach net-zero by 2060, Aramco and SABIC both announced targets to achieve operational net-zero by 2050, while ADNOC and QatarEnergy have both announced carbon reduction targets by 2030. Other regional players like Sipchem are developing or revising their sustainability agendas to reach net-zero targets.

The sheer scale of Scope 3 emissions data capturing makes them the most challenging to report on and remains the area with the biggest opportunity to contribute to net-zero targets. In this edition of Quarterly View, we investigate the data gap and how it may be overcome, the changing regulatory landscape seeking greater transparency from businesses, as well as the call for greater investments in infrastructure and technology to support the cause.

As always, I trust that you’ll enjoy reading this insightful publication.

Over the last few years, a confluence of global challenges, has brought to light, and exacerbated, industry wide change. Among them, the energy transition. The world is pivoting to a low-carbon future, and the demand for more sustainable businesses and greater transparency on carbon-emissions and climate change, is mounting.

For emission-intensive industries, like the energy and chemical sector, the path to net zero is an up-hill battle. To decarbonise, the industry will need to drastically reduce its carbon footprint across its value chain. This includes Scope 1, 2, and 3 emissions. While Scope 1 and 2 emissions are relatively straightforward to measure, and thereby monitor, Scope 3 emissions poses a fundamental challenge in visibility, that is hindering the industry’s progress in reaching climate targets and reducing its environmental impact.

As the adage goes, you cannot change what you cannot measure. Scope 3 emissions, which applies to all emissions that a business is indirectly responsible for across its value chain, is where the bulk of a company’s emissions are, but also where a company has less detailed reporting for. Why? Inaccessibility of data – a theme that we will explore in depth in the following sections.

The momentum to decarbonise across sectors is there, as evidenced by both countries and companies committing to meeting net zero targets by mid-century. However, the reality in getting to net zero will require tremendous change and an acceleration of investment. And in any good decision making, access to data as the first step.

Introduction

The chemical industry hasn’t been any different. A survey of chemical companies across seven sub-sectors in five continents, found that 97% have environmental impact reduction targets. In the GCC region, companies like Aramco and Sabic, have been placing sustainability at the forefront as well, continuously improving energy efficiency and pursuing low carbon energy solutions. As part of the Saudi Green Initiative, SABIC committed to carbon neutrality by 2050, with a very clear commitment to the Paris Agreement goals, focusing on meeting carbon neutrality from operations under SABIC's control.

But how can these targets be reached? Infrastructure upgrades and disruptive technologies can help reduce emissions, but they require large investments and lengthy implementation periods. As a result, businesses are looking for ways to remain financially competitive while also complying with new legislation and responding to pressure from stakeholders in the short-to-medium term. For chemical companies, a huge proportion of carbon emissions occur across the supply chain but without a good understanding of overall carbon footprint as a basis, it is difficult to find ways to reduce it.

The chemical industry is the largest industrial consumer of energy, but in terms of direct emissions, it ranks third after cement and iron and steel. Almost half of the chemical industry's energy consumption, and thus emissions, are related to feedstock obtained from the oil and gas industry, implying that a significant portion of the emissions are associated with upstream Scope 3 activities.

Currently, the most difficult issue for the industry is the availability and quality of emissions data, particularly those related to upstream and downstream activities, or Scope 3 emissions. Without resolving this issue, the industry will struggle to meet increasing regulatory pressures and stakeholder demands while remaining competitive. Though many chemical companies have announced targets for emissions reduction, achieving those targets will require a systemic change across the supply chain.

Could data be the key to identifying opportunities that result in real change in the chemical industry's emissions-reduction efforts?

The demand

for transparency

Emissions transparency has never been more vital, especially in the chemical industry. The US Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC) proposed rule changes earlier this year that, if implemented, will require companies registered with it (including publicly traded companies as well as many private ones) to disclose a variety of climate-related risks to the business as well as information about direct, indirect, and value chain greenhouse gas (GHG) emissions.

According to the SEC, “(t)hese proposals for GHG emissions disclosures would provide investors with decision-useful information to assess a registrant’s exposure to, and management of, climate-related risks, and in particular transition risks.”

There are more examples of proposals like these emerging globally. The European Commission implemented its Carbon Border Adjustment Mechanism for certain product imports in 2021, and many companies that operate globally or regionally have become increasingly concerned about their carbon footprints. Large investors expect businesses to be as forthcoming about their environmental performance as they are about their financial performance. When assessing the long-term risks of investing in a particular company, such "responsible investors" will consider environmental data.

"Many companies that operate globally or regionally have become increasingly concerned about their carbon footprints."

In 2020, 253 European funds modified their investment strategy or portfolio due to increased demand for sustainable investments. According to a survey, which included 300 high-net-worth (HNW) investors and business owners from the UAE, Saudi Arabia, Kuwait, and Oman, 81% of regional HNW investors said they already consider sustainability and ESG when making investment decisions. Sustainable investments now account for 33% of regional investment portfolios and investors expect this to rise to 52% in the next five years.

But it's not just investors who are becoming more interested in carbon-conscious businesses. Customers are increasingly demanding more environmentally-friendly products. 1 in 3 customers claim to have stopped purchasing certain brands or products due to ethical and sustainability concerns. To succeed in today’s global marketplace, sustainability must be a pillar in the way organisations do business.

The data gap

As regulatory, investor and consumer pressures mount, there is a need for the chemical industry to move faster. Firms can accelerate their efforts to meet their green targets by developing a clear plan. However, companies can only begin to make decisions that promote change once they have accurate baseline data on their carbon footprint. But how accessible is this data?

Companies report their carbon footprint by collecting data on the emissions in their operations. This is where Scopes 1, 2, and 3 of the Green House Gas Protocol (GHG) come into play. Consider it in terms of three types of emissions:

While a large proportion of carbon emissions for chemical companies occur throughout Scope 3, finding ways to reduce them is difficult without a good understanding of overall carbon footprint as a foundation.

For example, a converter of polypropylene (PP) resin should be able to calculate Scope 1 carbon emissions from processing pellets into a molded part or container. Obtaining a Scope 2 footprint from an electricity provider may be similarly more accessible.

But what about visibility into all the carbon used to make and transport those PP pellets, the Scope 3 emissions? Those pellets did not magically appear out of thin air — the molecules originally came from sources such as a barrel of crude oil or propane gas buried deep in the ground that was extracted and transformed into propylene and then into PP.

"But what about visibility into all the carbon used to make those PP pellets, the Scope 3 emissions? Those pellets did not magically appear out of thin air"

A variety of processes took place upstream to make that pellet, all of which have a carbon footprint. Figuring that out independently would be time-consuming at best and near impossible for most because there is not a one-size-fits-all answer to the Scope 3 carbon footprint of a carbon pellet.

As a result, while Scope 1 and 2 data is relatively accessible, Scope 3 visibility is virtually nonexistent.

Emissions transparency

While infrastructure and technology can provide solutions, these can take time and may require large investments. There is an urgent need for a method that can help bridge the gap and effect real change in the chemical industries' emissions reductions within supply chains.

For the first time, chemical and plastic companies can visualise the carbon emissions in their supply-chain right down to plant and supplier level. ICIS, chemical data specialists, working in partnership with Carbon Minds, environmental impact experts, have developed Supplier Carbon Footprints, a unique data set covering 71 chemicals that helps identify carbon emission hotpots and as such the opportunities for their reduction.

The data sheds light on CO2 emissions such as ethylene, propylene, styrene, and others, and it aids in meeting the reporting requirements of the chemical industries. It also identifies opportunities for reducing climate impacts within supply chains – and within that data lies the opportunity for business growth and resilience in a low-carbon future.

Take ethylene as an example; the various upstream processes involved in producing it vary both intra-regionally and internationally. According to ICIS and Carbon Minds analysis, the North American ethylene producer with the lowest Scope 3 emissions has a 21% lower carbon footprint than the most carbon-intensive. The global market has a much wider range, with the lowest emitter producing more than 11 times less carbon-intensively than the worst offender.

The movement toward carbon-footprint transparency in the supply chain provides an opportunity for those at the lower end of the carbon-intensity scale to market their products as "premium" or even "specialty," bringing with it additional margin and competitiveness.

Carbon-intensive producers of the same material, on the other hand, will struggle to maintain or grow business without offsetting high carbon-footprint material with lower prices. In many chemical markets, such stratification already exists around material purity, with high-purity grades commanding premiums.

This will also provide low-carbon commodity chemical producers with numerous opportunities to differentiate or rebrand their products with an environmentally conscious message.

Conclusion

There has been a worldwide call and response to reduce environmental impact, and despite the challenges of the sustainability transition, the chemical industry has demonstrated a strong willingness to respond. The inaccessibility of Scope 3 data has inhibited the progress and accuracy of reduction targets. It is impossible to make important decisions without a clear understanding of your impact. There is still much work to be done, but access to data is an important step forward that will allow the industry to be transparent and accountable.